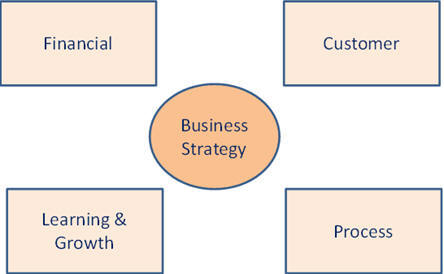

4.5 The Balanced Scorecard and Amazon.com

The Balanced Scorecard approach (Arthur Schneiderman (1987),

Kaplan and Norton (1992)) can be used within a firm as a method

for communicating business strategy.

It is a methodology that lets senior management

communicate and

implement business strategy at all levels of the

organization. When an

analyst outside the firm conducts financial statement analysis,

the Balanced Scorecard provides a framework for gaining a better

understanding of the firm’s business strategy.

Some important underlying themes to this approach are:

-

Describing business

strategy requires multiple dimensions because of the varying

emphasis given to different activities in the value chain

-

There needs to exist

some balance among these dimensions when an organization

implements its business model via its strategy.

-

Understanding major

firm decisions in terms of these multiple dimensions and

their balance is necessary for conducting meaningful

financial statement analysis.

Specifically, the Balanced Scorecard views the firm’s business

strategy from four perspectives:

Application to Amazon.com

In the 1990’s and up to the time of hiring Galli, Amazon’s

business strategy was unbalanced from a balanced scorecard

perspective. In particular Amazon was over-emphasizing the

“Customer” and “Learning and Growth” to the detriment of the

“Financial” and “Process” dimensions.

The “Financial” perspective requires looking at measures that

are relevant to the valuation of the company by shareholders.

These include items like return on equity, return on assets, and

stock price. For Amazon the ROE was deteriorating from 1998 to

1999 and was not a meaningful measure in 2000 because both the

numerator (Net Income) and denominator (Shareholders’ Equity)

were negative by 2000.

As a result, the DuPont decomposition of ROA (Return on

Assets) provides a meaningful measure.

In particular, the drivers of ROA (Profit Margin Ratio

and Asset Turnover Ratio) were very unstable under the GBF and

Customer Obsession strategy no matter what it costs strategy

that was implemented in 1999.

However, these ratios started to stabilize after

traditional cost constraints were imposed via old economy

techniques such as implementing a traditional master budget

cycle at Amazon.

The “Process” perspective refers to the

internal activities

performed by a firm. This includes identifying activities for

which it is important for the firm to excel and captures what in

financial statement analysis is referred to as “business

efficiency.” The most relevant item here to Amazon around

1998-2000 was the inventory ratios, such inventory turnover and

days to sales inventory given Amazon’s warehousing expansion

plans that were implemented in 1999.

From 1998 to 1999 the days to sell inventory increased

from 22.61 days to 59.69 days a whopping 264% increase in the

time inventory stayed with Amazon.

With the amount of capital tied up in inventory and

warehouses it is not surprising that at this time Amazon’s

related working capital ratios were also out of balance with

days to pay payable increasing from 86.85 to to 125.27 days or

just over 4-months on average to pay their creditors in 1999.

The impact from imposing cost constraints upon their

business strategy was almost immediate.

In 2000 efficiency picked up and the days to sell

inventory were almost halved to 30.26 days and days to pay

payables were reduced to 84.13 which was around 1998 levels.

The “Learning and Growth” perspectives refer to employee and

informational activities requiring innovation and continual

improvement. For Amazon some relevant ratios are that Sales

growth did decline from 1999 to 2000 (from 269% in 1999 to 168%

in 2000) but 168% is still consistent with a strategy of GBF.

In addition, the DuPont decomposition revealed that asset

turnover was increasing which was a positive trend in the light

of Amazon undertaking a significant expansion into warehousing.

As a result, employees of Amazon had to go down the

learning curve along this dimension.

The positive trend in asset turnover provides evidence in

support of this dimension.

Finally, the “Customer” perspective requires the identification

of performance metrics that measure the company’s success in

meeting customers’ expectations

viewed from the customer

or outsider’s perspective. Direct information on these is

available in the supporting notes to the financial statements as

well as other parts of the 10-K.

For example, measures of customer service, customer

ratings, customer loyalty or retention.

For Amazon the word “customer” is used often in its 10-K.

Further, in the supporting notes to their 1999 financials

Amazon reveal the following metrics:

Amazon disclosed the following in their 2000 10-K footnotes to

the statements. This

description contains some performance metrics for the Customer’s

perspective:

Growth in net sales in 1999 and 1998 reflects a significant

increase in units sold due to the growth of our customer

base, repeat purchases from existing customers, increased

international sales, and the introduction of new product

offerings. These new product offerings include music and

DVD/video in June and November of 1998, respectively, toys

and electronics in July 1999 and home improvement, software

and video games in November 1999. We increased our issuance

of promotional gift certificates to customers in 1999 to

promote new product lines, however, which partially offset

such growth in net sales. The Company had approximately 16.9

million, 6.2 million and 1.5 million cumulative customer

accounts as of December 31, 1999, 1998 and 1997,

respectively. The percentage of orders by repeat customers

increased from 64% in the fourth quarter of 1998 to 73% in

the fourth quarter of 1999. The increase in net sales in

1998 was also partially due to the launch of the UK and

German focused Web sites in October 1998.

Amazon’s 2000 10-K was a little less forthcoming on the customer

dimension although they reinforced their strategy in many parts

of the 10-K. For

example:

U.S. Books, Music and DVD/Video Segment. The U.S. Books,

Music and DVD/video segment had net sales of $1.7 billion,

$1.3 billion and $588 million in 2000, 1999 and 1998,

respectively. During 2000, we continued to enhance our book,

music, DVD and video stores by expanding selection, making

it easier to find items, and generally improving the

customer experience. In 2000, our Book store had the largest

pre-order in our history. Over 410,000 copies of "Harry

Potter and the Goblet of Fire" were pre-ordered on our sites

worldwide. We joined with Federal Express to provide

complementary upgrades to the first 250,000 customers who

ordered to ensure delivery on the day of release. In

addition, we launched an e-Books store, offering e-books in

Microsoft Reader format for PCs and laptops, as well as

downloadable e- audiobooks from our strategic partner,

Audible, Inc.

In

summary, in 1999 Amazon pursued GBF and Customer obsession

without imposing cost constraints on their strategy.

As a result when viewed from a Growth and Customer

perspective Amazon looked great. On the other hand when viewed

from their Financial and Process perspectives Amazon did not

look so good awful.

So the implementation of their strategy was not in balance.

However, with the steps taken in 2000, significant

improvements were made in relation to both the Financial and

Process dimensions.

Ultimately, Amazon’s stock price reflected these steps.

Amazon has chosen to both perform similar activities to its

rivals but in different

ways. At the

time, most of its competitors were traditional “bricks and

mortar” stores.

Choosing to be a virtual store on the World Wide Web allowed

Amazon in principle to offer the “Earth’s Biggest Selection.”

Conceptually this

illustrates why Porter’s original description of a value chain

was extended to embrace the world of electronic commerce by

Rayport and Sviokla (1994). They observed that the traditional

value chain model treated information processing as a supporting

element of the value-adding process and not as a

source of value itself.

However, the information generated by customer-centric entities

is a source of value for customer centric businesses such as

Amazon and Netflix.

This activity is driven by databases and predictive algorithms

designed to make it easier for customers to find reliable

product and service ratings.

In this development Rayport and Sviokla view the value chain as

a pair of chains – the traditional physical chain operating in

the physical world of

marketplace and

a virtual (or synthetic) chain that operates in the new

information world referred to as

marketspace.

This categorization provides a better description of the

business model for technology firms such as Amazon, versus a

traditional bricks and mortar firms such as Wal-Mart and Barnes

and Noble who choose to extend their businesses to have a

presence in both spaces.

More recently Amazon has added to it’s revenue streams by

offering e-commerce services to sellers and developers some of

whom compete directly against Amazon.com.

This item reflects another interesting extension of

Porter’s original static framework to a dynamic and more

“chainlike” in terms of linking back to itself, value chain.

Dynamic Value Chains and Amazon

The difference between a static and

dynamic value chains is that in a dynamic chain different

entities assume different positions on the chain depending upon

things like the time of day and a customers’ location.

For example Amazon and third party suppliers compete with

each other on Amazon’s own platform.

The dynamic dimension of Amazon’s value chain is

communicated in Item 1 of Amazon’s 2010 10-K.

Here they report two additional parts of their business

model:

Sellers

We

offer programs that enable sellers to sell their products on

our websites and their own branded websites and to fulfill

orders through us. We are not the seller of record in these

transactions, but instead earn fixed fees, revenue share

fees, per-unit activity fees, or some combination thereof.

Developers

We

serve developers through Amazon Web Services, which provides

access to technology infrastructure that developers can use

to enable virtually any type of business.

That is, seller services and

order-fulfillment part of Amazon’s business essentially competes

with Amazon’s own sales and procurement teams.

Similarly, the Web Services division enables other

businesses to compete with Amazon and others.

These are examples of Amazon embracing a dynamic value

chain in their business model.

Dynamic Value Chains and Risk

The risk facing entities in today’s

dynamic value chains is that a company can suddenly

drop out of the chain.

This was a problem that Border’s bookstores faced when

competing against Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Ironically, they were still the second largest “bricks

and mortar” bookstore when they lost their position in the

chain. This led to

the recent bankruptcy court events for Borders:.

July 22, 2011 a federal bankruptcy judge approved the

Borders Group’s plan to liquidate.

Borders at its height in 2003 operated 1,249

bookstores and 399 at the time of bankruptcy.

Both internal and external

factors are blamed for Border’s demise.

Clearly, online retailing and electronic book readers

were major factors.

For example, Border’s waited several years before it rolled out

it’s version of an e-reader called Kobo.

The other major “bricks-and-mortar” competitor, Barnes

and Noble, were much more proactive in their response to the

successes of Amazon’s Kindle.

Barnes and Noble developed it’s e-reader, the Nook which

today is competing successfully against the Kindle.

Borders also failed to

adapt to a dynamic external environment and badly timed their

expansion. They

expanded excessively around the same time period when Amazon was

generating significant performance gains from re-inventing the

implementation of their business model.

In addition, the world was rapidly embracing digital for

books, music and movies around this time.

Border’s ill-timed expansion resulted in relatively flat

sales along with rising costs.

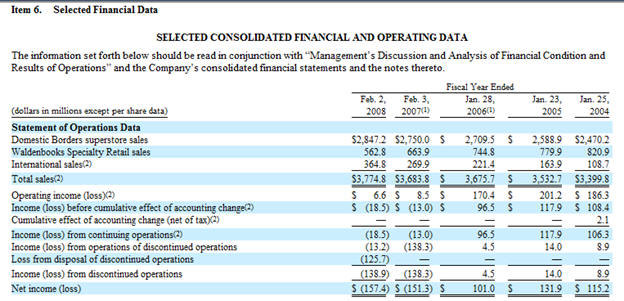

The following table from a 2008 10-K reflects these

problems.

Source:

Borders 2008 10-K, Item 6