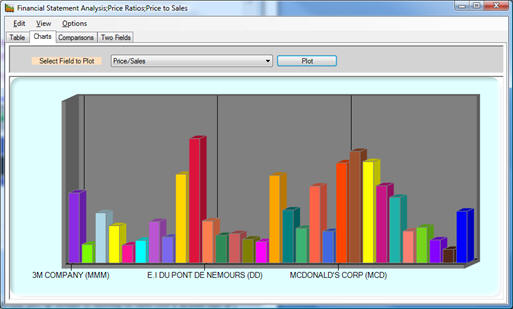

5.7 Price to Sales Ratio

Price/Sales Ratio

is a measure of the

number of

years to recover the stock price with zero sales

growth.

|

The price to sales ratio divides the stock price by sales per

share. This

multiple can then be applied to identify the relative value of

similar stocks. The

following plot from Valuation Tutor shows you the Price to Sales

Ratio for the stocks in the Dow Jones Industrial Average:

One rationale for working with the price to sales ratio is that

Sales Revenue is the top line of the income statement and thus

potential less subject to manipulation.

However, even though this top line item is usually subject to

less potential manipulation care must still be taken to read

item 7 in the 10-K, specifically the “Management’s Discussion

and Analysis (MD&A) and Forward Looking Statements, and Critical

Accounting Policy” section.

This section often provides a discussion of the stock’s

revenue recognition criteria.

Revenue recognition is subject to manipulation, and some

interesting insights into are provided by Mary-Jo Rebelo in

The Effect of the Dot-Com

Decline on Independent Accountants (The CPA Journal, May

2003).

“Revenue

recognition tops the list of creative accounting techniques

employed by many dot-coms. The decision to capitalize or

expense is inextricably intertwined with this point. A

company defers as many costs as possible. Capitalized costs

are reported as an asset on the balance sheet rather than an

expense on the profit-and-loss statement. Never before has

an entire industry had sales matter so much to its lenders

and investors.

For a website trading at 200 times expected sales, even a

small increase in reported revenues can translate into a

dramatic increase in market capitalization. Here are a few

examples of how it can be done:

The gross-up. Many dot-coms gross up revenues by reporting

the entire price a customer pays at their site even though

the company may actually keep only a small percentage of

that total amount.

Contra deals or barter. This method involves booking revenue

ahead of when the sale actually occurs. A dot-com exchanges

advertising space on its website for advertising space on

another to build brand recognition and use up excess

advertising capacity without using cash. GAAP requires

recording barter transactions at fair value, but does not

specify how to determine fair value. Many dot-coms have

treated such barter advertising deals as a sale, thereby

accelerating revenue as well as expenses.

Expenses. Dot-coms often manipulate the categorization of

expenses in an effort to report a more favorable operating

performance. Because dot-coms rarely report net profits, the

focus is on gross profits before the deduction of indirect

expenses. Dot-coms try to minimize direct expenses by

reclassifying them as indirect. The primary area for abuse

is coupons or discount vouchers, which are reported as

indirect expenses. By reducing direct expenses while

increasing indirect expenses, the company breaks even at the

gross profit level even though net losses are the same.

Additionally, fulfillment costs, the expenses associated

with warehousing, packaging, and shipping products, are used

in creative accounting.

Companies usually record fulfillment costs as a cost

of sales, but dot-coms classify fulfillment costs as a

marketing expense. This categorization allows dot-coms to

conceal operational expenses within the hefty marketing

costs that lenders or investors likely believe are

associated with establishing brand awareness.

Once these creative accounting techniques are combined, the

profit picture looks more promising. When dot-coms have

crashed, the creative accounting employed in an effort to

enhance financial performance has often been placed in the

lap of the outside accountant or auditor to explain and

justify.”

For this sample of stocks, observe the relationship between the

Price/Sales ratio and the Gross Margin.

It is clear that profit margin is a major driver of the

Price/Sales Revenue Ratio.

As a result, if there is a significant departure from

this relationship an analyst would use this as a flag that there

may be issues associated with how the company is recognizing its

sales. In the

previous section we summarized some of the revenue recognition

issues that can be explored if the price to sales ratio raises a

flag.